While the pandemic has placed pressure and strain on all members of society, it has had a profound and lesser acknowledged effect on unpaid and family carers. What has been the impact of COVID-19 on those looking after loved ones and how can we better support them in the future?

Words by Isabel O’Brien

The unpaid and family carers in our society can easily go unnoticed. Whether they are queuing in line at the pharmacy or helping their loved one out of a car, the world tends to not see their efforts, and recognition is lacking. For many, it is not a job – rather a privilege or a duty, but when we consider the responsibilities that caring can entail, we quickly realise that the role is physically, mentally, and emotionally demanding, and that we must work harder to support our informal caregivers.

“Caregivers are not taught the role. One day they are a wife, partner, working or not, but living a life without care. The next day their loved one comes home with cancer [or another diagnosis] and from that moment on they become a caregiver with no help or support,” explains Sharon Curtis, Caregiver and Charity Manager, The Swallows Head & Neck Cancer Charity.

While the pharmaceutical industry has become more patient-centric in recent years, their support for caregivers is notably underdeveloped, and the pandemic has only exacerbated the pressure and need for acknowledgement and growth in this realm.

“The need to provide emotional support to the patient has always been a critical part of caregiving, but the pandemic really showed how deeply this is felt by the carer,” says Vanessa Pott, Director, Global Patient Insights and Advocacy, Merck KGaA.

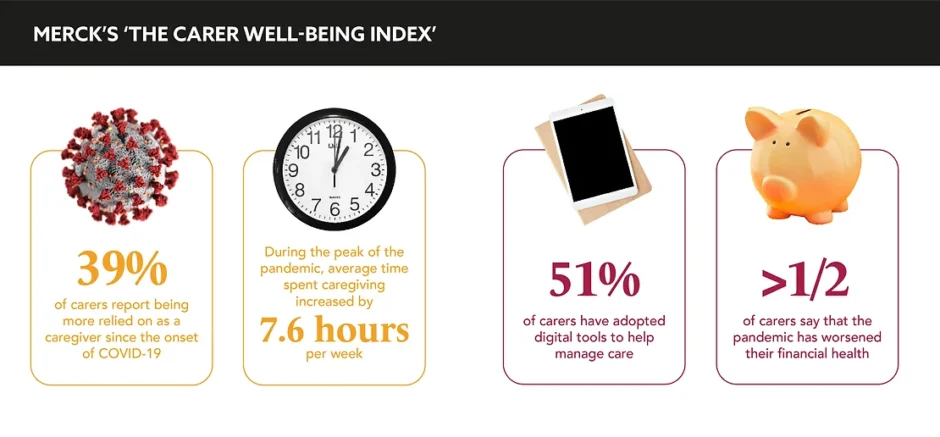

Pott’s team produced a report in 2021 called ‘The Carer Well-Being Index’ as part of a conscious effort to decipher the impact of the pandemic on the caregiver population. The report revealed that 61% of carers disclosed worsened emotional and mental health due to the pandemic, and only 17% reported talking to other carers to improve their mental well-being, despite the belief that this would help. “In a virtual world, carers may not have access to their own support networks, and visiting with friends and family becomes difficult, if not impossible,” explains Pott.

The flip from physical to remote healthcare delivery, although beneficial in some regards, has also physically separated patients from their physicians. Curtis raises the difficulty of “dealing with the news of cancer and consultant appointments via the new technology appointments.” Once the line goes dead and the consultant moves onto their next call, a caregiver becomes the sole source of support and guidance.

The impact has been especially severe on carers in low-to-middle-income countries (LMICs). Anil Patil, Founder and Executive Director, Carers Worldwide, expresses that in countries such as India, Nepal, and Bangladesh, financial factors have been a leading cause of emotional strain: “These countries have not implemented furlough schemes or anything similar,” he says. “Clearly, the pandemic has exacerbated a great emotional need on both the patient and the carer, and we all have a role to play in addressing it,” asserts Pott.

Curtis calls for an investment of time and resources to understand the world of the carer. “Pharmaceutical companies could look to understand the role of a caregiver and help fund projects that look to improve the caregiver journey, but more importantly the quality of life of the caregiver.” Pott agrees, stating: “Taking their needs and challenges into account when developing support materials and creating partnerships can help alleviate some of the challenges outlined in our report.”

In the short term, Anil suggests that the industry unite caregivers with relevant organisations that can offer emotional, financial, and practical support in the wake of COVID-19. “They could facilitate common platforms for the industry representatives, local service providers (private, charity, and not-for-profit), carers, and patients, to come together and plan for the COVID-19 recovery phase,” he says. Continuing to apply that in LMICs in particular: “This should reach not only the middle-class urban families, but also those living in rural areas.”

The pandemic has exacerbated a great emotional need on both the patient and the carer

While the industry must look to support those caring for the patients they serve, this mission must also look inwards. “Consider the fact that you have carers amongst the employees at your company, whether they’re vocal about their roles or not,” says Pott. “Providing opportunities for flexible work schedules and creating a culture where caregiving is recognised and respected can go a long way in ensuring carers are able to continue their professional careers while maintaining their caregiving responsibilities.” Pharma must create a culture in which caregivers feel comfortable to come forward and ask for support as they juggle this role alongside their professional responsibilities.

Creating a deeper understanding and visibility of all carers is a challenge, but pharma has a duty to its patients and its workers to illuminate and aid caregivers in their essential work. “When we start focussing not only on including the patient voice, but also the voice of caregivers, we gain important new insights that can help us develop better products and services,” concludes Pott. Sophisticated insights result in better treatments, adherence, and trial participation, rendering this mission far more than simply an act or symbolic gesture of altruism, but a necessary avenue to improve outcomes overall.